What mediums do you work in?

I use mostly ink and gouache. Some watercolor and graphite when the piece seems like it would benefit from those two added in for more texture or depth, but mostly ink and gouache.

What draws you to those mediums?

I think what drew me to drawing and working with paper originally was when I was around 10 years old I was really into the simplicity and flatness of medieval art, and the surrealness of it along with its desire to try to accurately portray something without good visual language to do so. It just always appealed to me. And the weird blending of reality and spirituality, like it was all the same—things that weren’t real were just as real in these paintings as things they could see and touch. And then I became more of an oil painter until I was about 30, and I stopped oil painting because my feeling was I was only oil painting because I felt it was the only way I would get anywhere within a fine art career, but drawing had always been my passion. And we lived in New York still and I would go to the Met and I still looked at a lot of Medieval art and Indian and Persian miniatures, and they all used gouache, so that was why when I started adding some painted color back into my work I decided to use gouache. Because it was really the art that had gotten me into art to start with.

So you were really young when you started making art.

Yeah, my stepfather was an artist, so we always had art supplies and art books in the house. I was more of a writer when I was younger, I wrote a lot before I had my daughter. When I had a child, writing changed for me. And I still write sometimes, but not like I used to write. I really just do traditional art now.

Why did you stop writing?

Writing things down feels a lot different when you know you have a child who’s going to grow up and read it. I’d always been a big journaler ever since I was really young, I have journals going back to when I was 6 years old. I threw out, like actually threw out, in the garbage, probably three quarters of them after she was born. Because I was like, I don’t want her to read any of this. I don’t want her to know I was thinking these things, I don’t want her to see this, I want this part of me to ever exist for her. And the chance of it happening is so high, like if something happened to me, it’s inevitable, she would get her hands on it, and read it. And that just changed it for me. So making visual art is a little more obtuse, like I’m still expressing myself, I know what it means, but everyone else has to guess what it means [laughs].

Looking at your art now, there’s still a lot of folk and mythological motifs — is that still from that medieval influence?

I think so, I mean folk art in general has always been a passion of mine. My grandmother taught me how to quilt and embroider when I was really young and so I’ve always loved craft and folk art. And some of my favorite artists are probably considered folk artists still. And I’ve always been interested in mythology and religion. Im personally agnostic, I was raised agnostic, but believing in things fascinates me because I am completely incapable of believing in things. So I’m fascinated by mythology and religion and people believing things that there is no evidence for. Because that’s just something I’m not capable of.

Are there other motifs like mythology that you return to?

The idea of ritual is also big for me, these things that we come together as communities and do repetitively. But I feel that we’ve kind of lost those. And the ones left are so commercial that they’ve become meaningless. So definitely the way ritual can build community and create common ground for people within a community. I’m also really into politics, so even though I think most people look at my work and don’t see politics, more work than people realize is me responding to current events, trying to process stories that I’m having a hard time digesting. I just use these very stylized kind of mythological motifs to parse them.

Do you want you work to be viewed as political, or is it more for yourself, to work through it?

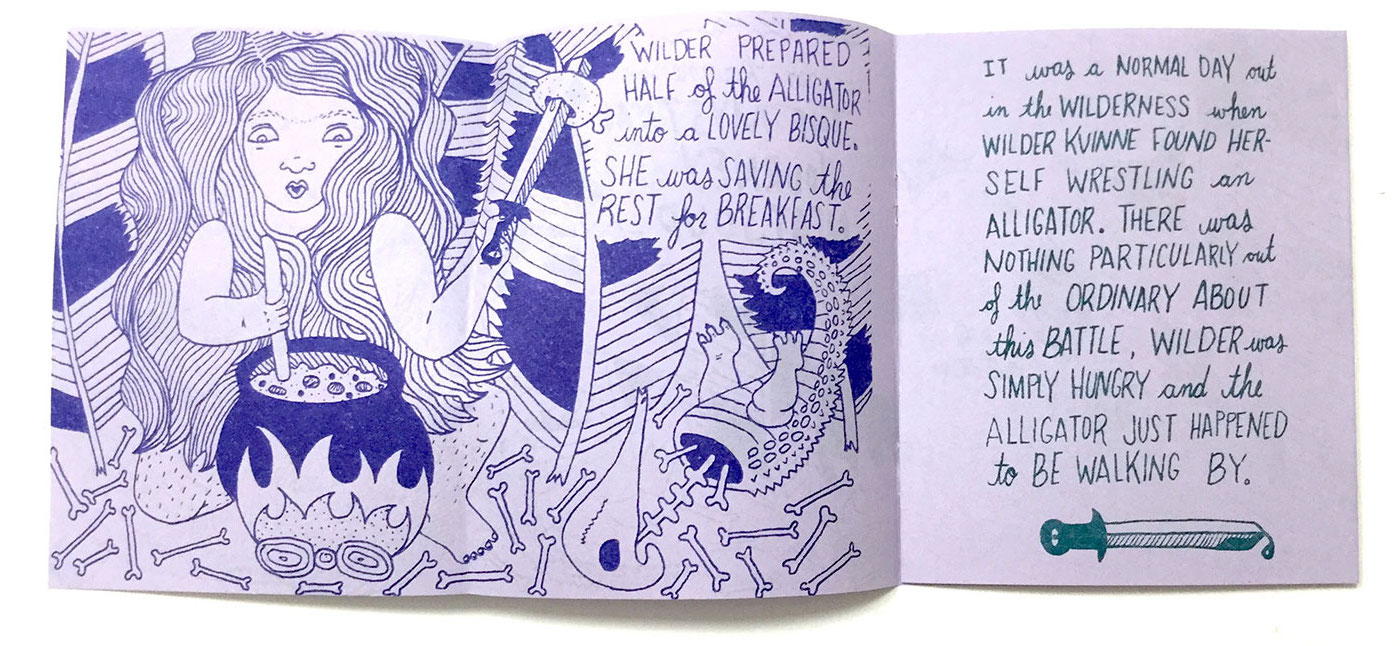

I do think there are ways that my work should be viewed as overtly politically, and then there are other parts of it I’m hoping it maybe resonates with people on a deeper level that they’re not always totally aware of when they’re looking at it. On the surface, I only paint women or women-identifying folks, and if I paint men, they’re all these weird creatures that aren’t human. They’re often stand-ins for more masculine sorts of people in my work, because to me, when I look at art, historic and modern, there’s a lot of very passive feminine energy in painting. You don’t see women in art doing shit. They’re usually just looking sexy. Or empty. But I am a lot more than that, and I want to see that in art. So I definitely am making work in response to that. That’s why there’s a lot of violence in my work, which is kind of cartoonish, it’s always with swords or daggers or very old school weaponry, but the idea is that I’m a woman but I still have anger. And to me, I want to see all of myself represented in art, not just the sexy part of myself, and that’s the most overtly political part of my work I’d say. I mean seriously, I think I’m going to go into a gallery one day, see one more vapid looking, you know, half pale underfed creature and I’m just going to slash it [laughs].

How would you describe your style?

I usually describe it as folk surrealism, because I’m very influenced by all types of folk art. And I love the idea of surrealism. Most of the surrealist painters I like, obviously, are the female which don’t get represented as much. Especially Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo, two amazing surrealist painters who also showed women very actively involved in their environment, and had kind of a folk art bent to their work as well. So I think I’m definitely continuing on in that vein of work.

If you could collaborate with any artist, living or dead, who would you pick?

Probably Henry Darger, I love that guy so much [laughs]. His work is fascinating to me, the fact he was created it without anyone knowing he was creating it is fascinating to me, the way he created work. I mean, I’m obviously like very inspired by him. Everything about him. He was a very sad figure, but to be able to actually meet him and talk to him and to like actually know what was going on would have been amazing.

Do you have a piece of work of your own that is your favorite?

I feel like mostly it’s whatever the newest piece is, because once I get few pieces away from a piece, I start seeing all the imperfections in it. I think there are pieces of work that are hard to say that they’re my favorite, but I see them as turning points. The most so would be this piece called And Each Was Cherished. It was this battle scene of women and small children fighting each other, just with pools of blood, but it’s very simplistic and colorful, and the women are all wearing primary color dresses with little dainty patterns on them. But it’s probably the most violent piece I’ve drawn. The idea for me was that all the violence and wars you’re always hearing about, you start to not think of it the same way. And what would make war more immediate to us? What would make us stop and be like “holy crap, that is too much”. And I was like, oh, if a whole bunch of mothers and babies were fighting each other violently, that’s what. Like you look at that and you say, “that is some messed up stuff”. But the point is that every person that dies in war has a mother, and was a child. That is who is being destroyed by these wars. It isn’t just the people dying in the war, you’re destroying that entire family, and cultures. And the destruction is endless… So I think it was the first time I had this feeling that I needed to express something that complex, and that I successfully executed it. And when I look at the painting now, I’m like, oh my god, that rendering is terrible. I’m much better at rendering things now, and I’m much better at doing what was trying to do in that piece. So it’s hard to say it’s my favorite piece. But I feel like its a piece that successfully got through what I was trying to get through.

What’s the most important part of your artmaking process?

There’s time where I’m kinda sitting quietly, it’s usually when I’m on the bus or in the shower, just doing other things and letting my mind follow the tangent that I’m working on, and that’s when I really start realizing the next part of this series, or the next thing that I should work on. Those moments of just contemplation or playing around with my sketchbook, when I’m just thinking about what comes next. The actual art making after those moments have happened is almost straightforward once I know what I’m working on. I mean there are parts of it that are harder than others, but since my work is so narrative, it’s kind of like coming up with the next part of the story.

Do you ever find it hard to share art with people?

I used to, I think it used to be this cyclical thing where I’d show people and then get discouraged, and then I’d feel like shit – and that still happens, but not to the extent that it used to. I kind of jokingly, a few years ago, said that my goal was to get a rejection every single day, because then the rejection is the goal. To get a rejection everyday you really have to be putting yourself out there a lot, so I kinda just changed my perspective on it. So I try not to focus too much on what other people think about it. I just keep making work, and the only way that I can keep making work is that I share work and that people hopefully buy some of it, because it’s expensive to keep making work [laughs]. I just try to think of it that way, more than worrying about whether people like it.

What’s your history with the IPRC?

I’ve been volunteering here for almost three and a half years now. I moved to Portland almost four years ago, and I knew about the IPRC before I moved here, and so I was like, if we move I’m going to volunteer at the IPRC, and I’m going to make friends, and it’s going to be the best. So I pretty much became a volunteer because I wanted to make friends, but then I just love this place. I mean, pretty much every friend I made in Portland is because of the IPRC. It’s been a big part of my life since I moved. And I like moving a lot, and I want to move again probably in the future, but the IPRC is the one thing that will maybe keep me here longer.

How would you like to see it grow?

I would like to just see more people using the space. I just wish that Portlanders realize that we want to treasure this. I have lived all over the country and have never had a resource like this. I mean, we have a lot of members, but I just don’t think people realize what they can get out of this place, from the perspective of making things but also like the community that you get from being a part of it.

What would you tell someone who maybe hasn’t made art before but wants to start?

Make. Art. Every. Day. Like really, I wish someone had said that to me when I was 17. I mean, I loved art and I knew that’s what I wanted to do, but I would get caught up in my life and I wouldn’t make art everyday. When I look at my drawing skill today, I know that I’m where I am because I’ve been literally drawing every day for the last ten years. And I wouldn’t be getting the opportunities I’m getting now if I didn’t follow that advice. Don’t judge it, don’t worry about if you even know what you want – draw the same thing every fucking day, it doesn’t matter! Don’t make excuses, don’t think about making art, don’t worry if people like it – you don’t even have to share it. Just draw something everyday! Because if you do anything every day, you will get better at it. It doesn’t matter what it is. You will improve. Get a nice little sketchbook, get a couple pens you like drawing with, and just every day make the goal filling up one page. The more you make art, the more it becomes clear what you want to do with it. Thinking about it, you just get in this fear cycle – it’s useless. And people say all the time, “I wish I could draw like you”, and I’m, well, you could, you just have to start drawing! I was shitty at it at the beginning, and arguably, in ten years from now I will look back at today’s drawings and I’ll be like, that’s a bunch of crap! But I’m not going to get to where I’m supposed to be ten years from now if I don’t make the art I’m making today. I feel like that’s all art school needs to be for people. Just someone sitting there going, “Ok, make another drawing today. Ok, do it again.” They don’t need anything else. That’s it. That’s the secret of art.

Just out of curiosity: do you think about the journals you threw away?

I do, I do think about them. I think now that my daughter is 15 and is becoming an adult, and I can see who she is, I’m like, ok, I should have kept them. I would like to read them, because again I was only 26 when I made this decision, and I’m 41 now, so now I just can’t remember that time anymore. I just thought I would always remember all the little nuances of everything – like I have a vague idea of what it was like to be 16 and I know remotely what I was doing – but I want to remember why I was doing everything I was. And that’s why I kept the journals to start with. But I did keep the journals that I felt were too important of transition times for me, that I needed to keep them. Now actually thinking ahead, I’d like to start journaling again. I want my daughter to know what I was thinking when I’m gone.

Erika Rier is a self-taught artist working mostly in inks and paints on paper in a style she calls folk surrealism. After many years of oil painting and designing clothes, she shifted her focus to works on paper. Writing was her first love, and she still secretly writes fiction, but never poetry anymore. Having lived in Maine, Vermont, Connecticut, NYC, Arizona and Washington, Erika now resides in Portland, OR. She also has one of each of the following: a husband, a daughter, and a cat. erikarier.com. Instagram: erika_rier Etsy: ErikaRier

All images are used by permission of the artist. Interview by Ella Stewart.